2. The implementation of international account planning

“The development of an effective international campaign, standardised or adapted, requires careful management and good communications. If a campaign fails, this is often because implementation was not effective” (Mooij 1991, p384).

The effectivity of international account planning is closely connected to the organisational attachment of decision-making processes, the adaptation of procedures, the task assignment and the attitude of employees (Waltermann 1989, p238). This results in two central duties within the scope of implementation:

- To define which procedures of international account planning within the group can be

standardised and

- To overcome anti-planning biases by the involved.

The above analysis of international account planning showed that many tasks can be standardised.

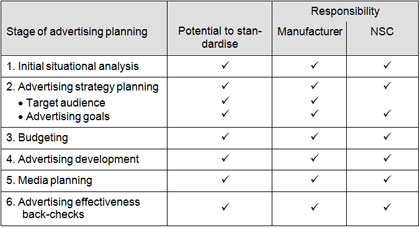

Table 5: International advertising planning: potential standardisation responsibilities.

At first glance, the centralised organisational structure of automotive companies favours standardised account planning. The power of manufacturers not only manifests itself in its authority, but also in the advantage in know-how with regard to marketing processes and its higher capacity of personnel. This, however, is encountered by national sales companies being generally organized in profit centres and only accountable to the manufacturer in view of the overall result. Marketing decisions are taken on the spot due to the higher marketability.

The question about the capability of standardisation thus ranges on the one hand within the area of conflict to use centrally residing know-how and on the other hand it lies in the knowledge of the market as well as in flexibility (Mooij 1993, p337 f.).

The centralisation of the planning skills and decision-making authority is not reasonable because it would require extensive control mechanisms and would have a demotivating effect on local management. If the manufacturer imposes his planning techniques on the national sales companies, this meets with refusal, an effect which is known under the keyword “not-invented-here-syndrome” (Landwehr 1988, p208).

The refusal is even stronger, the higher the motivation of local managers is, the more important the procedures to be standardised are, the more distinctive their democratic attitude is and the higher they esteem their proper skills. In these cases, standard processes are seen as restraint through conformity impeding deployment. There is a danger of bureaucratic behaviour resulting from it which anticipates flexible reaction to the market development and thus contradicts the sense of the national sales companies’ activities (Kreutzer 1986, p42 ff.).

The anti-planning biases induced by standard processes can be prevented by cooperation between manufacturer and national sales companies. Several methods are suggested (Berndt et al. 2003, p292 f.):

- regular meetings,

- international coordination teams,

- use a lead-country approach,

- use a network approach.

One of the first steps a company can take to coordinate international advertising planning is to organise regular meetings, with the manufacturer and its national sales companies sat around one table. Apart from getting to know each other, dispelling prejudices and improving the atmosphere, regular meetings facilitate inter-company cooperation. For example, countries can decide whether it would make sense to adopt a successful advertising campaign from another importer. This approach also reduces complexity – meetings tend to be consultative; participants get a feel for how flexible the others are. However, a danger with this approach is that meetings can become monotonous and waste time.

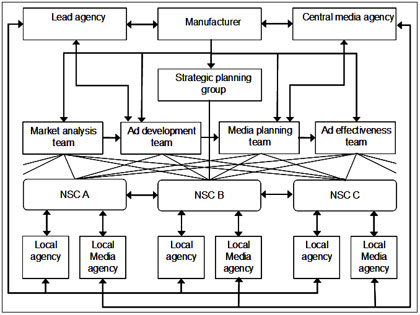

A key factor with international coordination teams is the level of cooperation between the manufacturer and its national sales companies. With this approach the focus is on identifying which stages of the international advertising planning process can be delegated and to whom. The coordination teams themselves should be made up of staff from the manufacturer and its national sales companies. These feed into a strategic planning group whose task is to define the advertising strategy.

Figure 14: International coordination teams (from Kreutzer 1986, p14).

The advantage with international coordination teams is that they reduce the burden on the manufacturer without delegating strategic authority. They also take into account local market knowledge and allow the company to transfer know-how throughout the group. The downside is that people can become quite removed from day-to-day business. As a result, national sales companies will only agree to this approach if, in return, they are allowed to have a say in strategic planning.

With the lead country approach, one company within the group is turned into a 'first among equals'. It is then agreed how long they will manage international advertising planning and where. Under their management, each country looks after specific parts of the planning process. The output of work is used as a template. Countries may deviate from guidelines laid down within the template but only under exceptional circumstances. The lead country does not necessarily have to be the manufacturer. For example, it could be the NSC most affected by the launch of a new model (Mooij 1991, p 346). Alternatively, the country chosen could depend on marketing skills, resources or individual market knowledge. It could even be company politics – the carmaker might want to bring a specific NSC to the fore. The advantage of the lead country approach is that it is more participative and taps more efficiently into skills in individual countries.

One disadvantage is that the lead country might be rejected by the national sales companies feeding into it – again, before they cooperate, they may want more say in strategic decision-making. Another risk arises when staff from the central organization is kept out of the process, as this undermines the manufacturer's overall strategic authority. Further, if the lead country only holds bottom-line responsibility for its own country, there is a significant risk that it will neglect the interests of other parties. To get round this, the company would have to completely reallocate responsibilities. Given ownership patterns, this is currently almost unthinkable for most European national sales companies.

As the name implies, the network approach involves a close-knit network encompassing both manufacturer and its national sales companies. Responsibilities are matched up carefully between each country; each part of the company can be given similar functions. The allocation of responsibilities depends on the comparative cost advantages. The good thing about the network approach is that it is highly efficient and involves a broad variety of people. The less good thing is that each part of the organisation has to be fairly similar in terms of resource. For this reason, given the differing levels of resources in the automotive sector, this approach is not yet a viable option. These four cooperative models – between the manufacturer and its national sales companies – can enable companies to reduce internal resistance to planning – even before processes are standardised. Actually sitting down together to work out the best approach to international advertising planning is, in itself, a good way to pull in people from various parts of the business. It can also be central to winning people over for the final standard processes (Kreutzer 1989, p531). To do this, you need a step-by-step introduction plan whereby each stage of the plan is designed to help overcome objections.

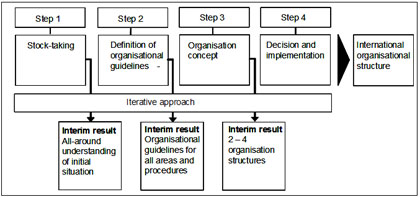

Figure 15: Plan for the step-by-step standardisation of processes in international advertising planning (Source: Berndt et al. 2003, p308).

- The first step is an international stock-taking exercise to see how advertising planning works at present.

- Next, the company should identify the areas in which it could cooperate. It then creates new standardised working processes hand-in-hand with responsibilities (see table 5). To gain acceptance at this early stage, it needs to keep working processes simple and demonstrate to national sales companies what is in it for them (Landwehr 1988, p221 f.).

- As the plan progresses there should be built-in back-checks. The first time round, it is not so much about restructuring the organisation as allowing people to adjust to the new way of thinking. Once the company has established uniform planning criteria and laid down fundamental planning procedures, it can move on to the higher, organisational structure and the allocation of responsibilities – and tackle issues such as international coordination teams.

- Once the project team has worked up first-stage guidelines and organisational structures, it can then use the launch of a new car model to introduce the new approach to the other national sales companies.

From now on, every time the company goes through the planning process, the standardisation process can be spread out step-by-step to encompass all activities within the international advertising planning process. In the interests of pushing things forward, it makes sense to do this by targeting the importer most likely to cause trouble – and make it the lead country. By turning it into both originator and recipient of planned changes it is more likely to identify with the overall aims of standard processes. This also helps break down resistance throughout the international organisation. The timing and aims of the process should be moved along by higher level management, as much as anything to emphasise the significance of the project in writing. Further, the manufacturer can provide input from planning experts to ensure that the methods being applied match quality criteria (Landwehr 1988, p243).

When standardising processes, it is particularly important to provide the right management information system to make sure everybody knows what is happening (Berndt et al. 2003, p171; Kreutzer 1986, p 24). A good example of this is the Volkswagen Marketing Database which provides national sales companies with online access to a variety of information on international advertising planning, such as competitive advertising (for analysing the initial situation), briefing documents (for planning advertising strategies), guidelines, press ads and pictures for executions.

Figure 16: The Volkswagen Marketing Database (Source: Volkswagen AG, Wolfsburg).

When standardising processes it is essential to supply people with the right facts (Mooij 1991, p351). In this respect, introducing the marketing database at Volkswagen actually paved the way for the standardisation of processes and content. Ten years later, the database is used by 98% of Volkswagen national sales companies. Indeed, prior to its introduction the company recognised that the dialogue with their national sales companies had not come about as a result of international advertising planning – it was a prerequisite.

As Stanley Pollitt, the father of account planning in the UK, once put it: 'Planning is creative thinking based on information.'

Further Chapters

- Standardised international account planning

- International analysis of the initial situation

- International advertising strategy

- International advertising budget planning

- International planning of advertising design

- International media planning

- International advertising control

- The implementation of international

account planning